Effective communication in safety is the energy, the vibration that travels through every part of your safety and health program. Reporting, incident reviews, describing hazards and risks, finding and fixing hazards, coaching, conversations, auditing, giving feedback, training, responding to emergencies and leadership all require energetic input from participants. Pulsating, highly-charged communication reverberates through your culture. Low energy, poorly executed communications will decrease engagement, leave hazards undiscovered, hurt morale and make management support more difficult to obtain.

The stakes are even higher. Communicating effectively can be and is a matter of life or death.

Clear, concise, objective, and accurate communication is the difference between success and failure for many safety activities: behavior-based observation programs, training programs, safety meetings, presentations to management, incident and near miss/close call reporting, incident investigations including serious injuries and fatalities, finding and fixing hazards, pre-shift briefings or huddles, job safety analyses, risk assessments, and how suggestions, complaints and concerns are handled.

Safety’s line of communication also must be tailored to an array of audiences: managers, supervisors, employees, contractors, temporary workers, staffing agencies, compliance inspectors, new hires, 30-year vets and non-English speaking workers.

Given the stakes and the challenges, good communication should be a core competency, valued and emphasized. But it is easy to take communicating for granted. Talk. Talk. Talk. We all have been messaging and developing our styles of communication since shortly after we began to walk.

Think how poor communication, rushed, improvised or ambiguous, causes confusion, misunderstanding, delays, inaction, anger, apathy, eye-rolling and head-scratching. It leads to incidents or near misses/close calls. Damages teamwork, attitudes, planning, hazard abatement, and bringing audits to closure. It can alienate management from safety activities.

Communication Is The Connection

Communication connections are important to safety work today more than ever due to technology advances and the so-called “connected worker.” Workers using wearables or hand-held devices to report incidents, near misses, hazards and hazardous conditions have the potential to communicate with more frequency than ever before, on the spot, in real time.

- Is the reporting/communicating clear, concise and jargon-free?

- Is it accurate in its descriptions? Detailed?

- Is it free of cognitive biases, blind spots, and opinion and judgments?

- Does it stick to the facts and avoid subjectivity?

- Does it use critical thinking to analyze and interpret?

- Can the messaging be comprehended quickly and easily?

- Does the reporting/communicating include solutions to problems and state actions to be taken?

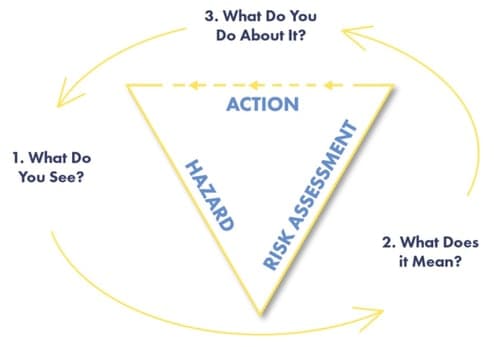

Many issues involving safety communication should concisely describe:

- What has been observed (a hazardous condition, an incident, a near miss/close call)?

- What does the object of the observation mean (analysis and interpretation concludes a serious risk exists)?

- What action needs to be taken to ensure safety (immediate medical attention is needed)?

Effective communication: “This is Joe Wilcox. It is 7:35 a.m. and I am observing a water leak in the southwest corner of Warehouse C roof after last night’s heavy rain. Water is flowing, not dripping, from the roof to the floor. A puddle about six square feet is expanding on the floor. Stacks of paper rolls are wet. Maintenance needs to patch the roof immediately and housekeeping needs to rope off the wet floor areas, vacuum up the water, and disperse spill absorbents to prevent slips and falls.”

Ineffective communication: “Uh, hello? I think I see a water leak coming from somewhere, maybe the roof. There’s a puddle on the floor. Where am I? Uh, over by the corner of the warehouse. How much water? Uh, I don’t see any fish, heh heh, yet but it’s getting bigger. Is somebody going to do something about this?”

Learning To Communicate Effectively

Numerous safety communication courses focus on interpersonal communications. Sending positive or negative relationship messages, supporting leadership, having an open-door policy, behaviors of senders and receivers, characteristics of voice and body language.

At COVE: Center of Visual Expertise the focus is on specific safety tasks and related communications. Workshop participants learn how to identify and assess hazards — and importantly — how to effectively communicate descriptions of the hazards they have found, the risk potential of those hazards, and after analyzing and interpreting the hazardous condition, what action needs to be taken. Similar communication skills are applied to safety leadership and incident investigations, including serious injuries and fatalities.

COVE workshops highlight three keys for effective communication:

- Avoid Subjective Language — Subjectivity Introduces variability in how others may interpret your message.

- Say What You See, Not What You Think — Using objective language avoids communicating your interpretation without giving the listener a set of facts they can draw interpretation from.

- Don’t Confuse the Message with Too Many Words — The message can get easily lost if we confuse or wear out the listener with a long dialog.

Held at the Toledo Museum of Art, participants hone their ability to give accurate descriptions by describing to each other pieces of art – paintings, sculptures, etc. Clarity and conciseness are emphasized, along with leaving out any jargon. The Elements of Art give communicators a common language for descriptions that note color, lines, shapes, space, and texture. These are observed facts; there is no room for subjective opinions or judgments. Red is red. A line is straight or crooked. Shapes are described. Dimensions of space are stated as fact. Texture is present or absent.

Critical thinking skills are discussed and employed by workshop participants: gathering all relevant information; analysis; interpretation; evaluation; problem-solving and decision making. Critical thinking boosts communication confidence. Safety communicators are prepared with information, analysis and potential solutions.

Critical thinking also makes you aware of your own biases that can shade or distort your reporting, descriptions, analyses and solutions. For example, the confirmation bias makes you tend to be influenced by safety information that reinforces your existing beliefs or assumptions. Hindsight bias might have you saying you knew all along forklift lanes had faded and a pedestrian would get hit — after the incident occurred. The anchoring bias can distort incident investigations by giving too much weight to the first piece of information collected about the incident.

Think about it. Safety issues often demand immediate action. Something needs to be done. A worker is down. Lighting is out. A hail storm is coming. Evacuate the building. A trench needs better shoring. The contractor’s guys aren’t wearing fall protection. Office staff is complaining about a smell. Boxes are stacked too high. We’ve lost contact with Ed in confined space C.

These situations demand concise communication. Speed, response time could mean the difference between life and death. Stick to the facts. Keep your message short. Offer clarity, not opinions or speculation. State what direct action will be done.

Imagine a workforce trained to communicate concisely, directly, clearly, with no jargon and with action steps included. A common language is used, reducing misunderstandings and ambiguity. This is how Visual Literacy principles, taught in COVE workshops, avoid communication breakdowns. The stakes in safety are too high for misunderstandings, hesitancy, delays and confusion – for anything less than effective communication skills.